How come the Avenue ends with a Place for cultural institutions – rather than legal, commercial or municipal buildings?

One answer might be found in a link between those who commissioned the Place and the evangelical Moravian revival movement, the Evangelical Brethren’s Congregation in Gothenburg.

For this movement, the focus was not on obedience or conversion. It was on a personal and emotional relationship with Jesus – a “God of joy”. Worship services were filled with music, singing and gratitude, rather than laws about guilt and sin.

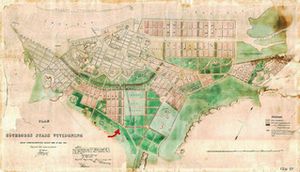

Several of the City´s most influential merchant families – including the Ekmans, Santessons, Kullbergs, Kjellbergs, Aurells and the Brusewitz family – were members of this movement. Later, many of these also settled in the newly developed urban area around the Place. Jonas Kjellberg, who donated one million kronor in bonds for the construction of the Art Museum, was a descendant of an early member of the same religious community.

The first Moravian congregation in the City was founded in the 1750s. It challenged the social norms of its time: opening schools for the poor, then a girls’ school; women were included in the congregation’s leadership from as early as 1752 and could be ordained from 1758.

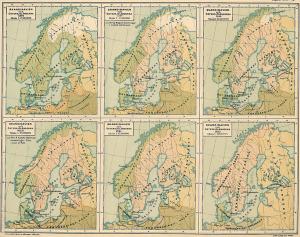

The small town of Christiansfeld in Denmark, was planned as a Moravian settlement from the late 18th century. It is known for its straight, tree-lined streets, yellow brick houses in simple, unified architecture, and a central square with a well at its heart.

Central to Moravian belief was the value of light, music, art, education and generosity. These ideals can seem echoed in the temple-like architecture of the Art Museum. In an article in Sciascope 7, Stina Hagelqvist describes its grand vaulted arcade as "both a beginning and an end – a threshold between physical everyday realms and metaphysical realms. And the bronze doors by Carl Milles, depicting Apollo and Athena in high relief, aimed to further strengthen this temple-like impression: one leaves the realm of mortals and enters into a different reality."

Everyday life gives way to ritual and reverence – with art at the centre.

Was the city of that time not only divided by social class, but also split in its view of art and culture? If so – what does that say about the Place? Could it, in fact, be a display of power – one side asserting itself over the other?

S. Hagelqvist, Från Tempel till Fabrik ( From Temple to Factory) Skiascope 7, ed. K. Arvidsson, Göteborgs Konstmuseum.

Photo: Göteborgs Konstmuseum 1928, photo from the Göteborgs Konstmuseum archive.