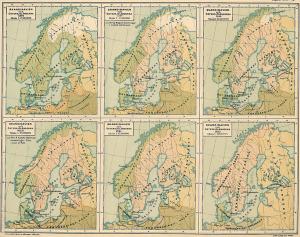

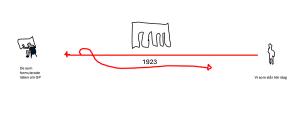

I find this map, showing the southern parts of the Nordic region in 1658. But not as we are used to seeing our maps: this one is tilted almost 90 degrees.

Now, southern Sweden stretches out horizontally. In front of it, Denmark appears almost like two large islands. One of them points toward the coast of Norway, to the left in the image.

And the city? You’ll find it in the middle of the drawing, directly below the large lake Vättern. I’ve marked it with a red ring.

This simple twist shifts the focus: the waterways now seem most essential. Suddenly, it becomes clear why building a new city along the river would have seemed like a smart move for the king. At the time, all transport and trade depended on ships.

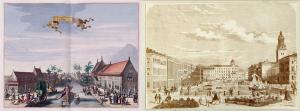

But the map reveals something else, too: drawings of the harbor cities along these coasts—key hubs for import and export in the 17th and 18th centuries. They all seem to follow one basic model: fortifications with thick defensive walls. These cities were expecting enemies. Yet, at the same time, they remained open to trade, to both import and export.

This historic period reminds me of the Monopoly* game: the players—kings, constantly at war, seizing and recapturing territory from one another—competing for dominance by controlling strategic points where customs could be charged.

In my work, I need to keep this in mind: the city was born with a clear purpose. It was meant to secure and defend one of those very strategic stretches—and to act as a tool for claiming a share in the region’s trade. The king needed to finance his wars of expansion.

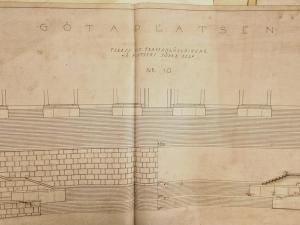

Can this foundational fact be read in the physical form of the Place? In the scale? In the victorious God in the fountain?

*Monopoly was created in 1903 by the American anti-monopolist Lizzie Magie.

Image: Sedes Bello Dana suecici ao 1658, map, copper engraving by Å. Bandolär. Gothenburg City Museum, Collection ID: GM A7848.