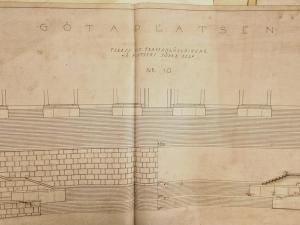

The Place opens up a very concrete space within the city. Yet this space also feels like an image. As if the grand staircase and imposing architecture are hinting at something otherworldly – a sense of higher meaning.

At the same time, I see no references to God. Which, in itself, might seem a little strange: the City was, by definition, Protestant. Luther’s words about “one Lord, one faith, one baptism, one God and Father of all”, were taken very seriously here. Priests conducted day-long catechism examinations in schools and on farms. The Little Catechism was mandatory reading in schools from 1572 until as late as 1919. So it would surely have made sense to find references to God – and to the One Church – at the most prominent Place in the City.

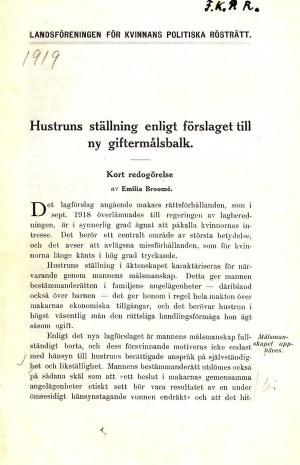

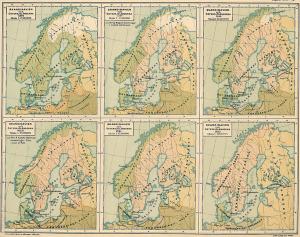

But by 1919, when the City decided to construct the Place, the harbour had already reshaped this context. The City had become a cosmopolis – a place where different languages, styles of dress, and religious beliefs could coexist. The idea of “a unified universal church” had been challenged, both within and beyond the state church. Two Jewish congregations and a number of revivalist movements – Methodists, Baptists, Schartauans and Moravians – had not only introduced alternative images of God, but had also helped reshape the city’s political landscape.

Planning a large, shared Place in the midst of such a diversity of worldviews and beliefs can hardly have been straightforward. Perhaps that’s why the City chose to take a detour – and dedicate The Place to Art ? Not to God, and not to the King either.

But what is the higher meaning that still seems to linger here? Is it about faith- as such? Or is it, quite simply, about us – about human beings as individuals, capable of understanding and interpreting the world we live in?

Swedish Church – Gothenburg Diocese, Sacred Spaces, accessed 2025. www.svenskakyrkan.se/goteborgsstift/heliga-rum

Image: Catechetical Meeting, painting by Knut Ander. Wikimedia Public Domain.