Can one point to a beginning – a kind of "seed" for the identity and role of the Place? Was there something here before, from which the Place organically emerged?

I put these questions to Lars Jadelius – retired professor of architecture, historian, and cultural scholar. He answers without hesitation: the “seed” may very well have been an unusual decision made by the City when the old city walls were torn down in the 19th century.

The decision was to preserve the former military training grounds on the far side of the moat and transform them into a park. This, in turn, paved the way for the establishment of the Garden Society – a new kind of social space, embedded in nature.

But Lars offers me two additional “seeds” for the Place’s identity: two ideals that were thoroughly modern at the time – “the Green” and “the Villa.”

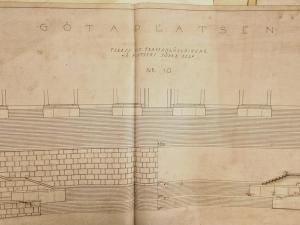

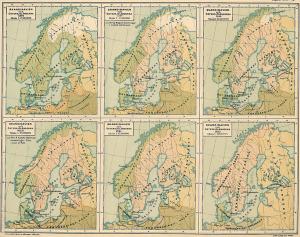

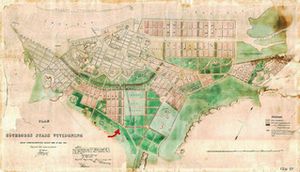

The Crown had granted the City several plots of land to help secure its food supply. These were initially used for sparsely built farming estates – so-called landerier. A whole row of them stretched along what was then the city’s southern approach – Södra Vägen.

During the 18th century, these estates were taken over by the City’s wealthy merchant families, who transformed them into manor-like summer retreats – in effect, villas surrounded by large gardens. And when Nya Allén was planned, a series of large, freestanding villas were placed within the newly designed green space, intended as homes for the urban elite.

Later, when the City replace the landerier with an entirely new avenue, “the Green” was once again taken up as a guiding principle. The Avenue would be lined with rows of trees. And each building alongside the Avenue, would have a front garden.

One final factor may also have shaped the Place’s current identity and role:

An early owner of Lorensberg – one of the landerier – was granted permission to convert his summer residence into an inn. A later owner turned that inn into a variety theatre and an open-air dance venue. It became a popular meeting place for the City’s affluent families. Roughly where the Poseidon statue stands today, there was also a shooting range operated by the Sharpshooting Society from the mid-19th century. When a major fire destroyed the area in 1864, the owner was granted permission to build an even larger restaurant, a permanent circus building, and an English-style park.

The photograph you see here was taken in that very park towards the end of the 19th century.

I now seems fair to say, that the Place carries forward a pre-existing identity. For a long time, people had gathered here – using the area for the very opposite of hard, physical labour. It was already a zone of greenery, leisure, and social activity – always framed by the logic of strolling.

Does this context also bind the Place in the future? Will it always stand in contrast to the idea of the commons? Will it always rest on exclusion?

Screen capture: Journalfilm F2331, Lorensberg then and now (Equestrian club's prize jumping. Riders in hilly terrain). Hasselblads Fotografiska AB, 1916.