I read a quote from the theologian Anders Jarlert, stating that no individual "has so profoundly influenced church life in southern and western Sweden during the 118th, 19th and 20th centuries, as Henric Schartau”.

Henric was ordained a priest in 1780 within the state Church. At the time, it, mediated an image of God, and of the Chruch, as "equal for all." But his own faith was rooted in a different, profoundly subjective and emotional experience. A process of deep despair, which had led him "out of respectable vanity" to become "captivated" by the Bible. For the rest of his life, he would consistently insist that true faith must rest upon such a deeply personal conversion.

Yet Henric Schartau chose to remain within the church. And Schartauanism never grew into a free church movement but remains a movement within this church, preaching a stronger emphasis on the individual “ salvation through Grace" - a carefully planned passage through four different psychological stages. They help Man recognise, how God has given us reason, so we can understand why and how we can submit to His laws. Laws, based on notions of faithfulness and unfaithfulness, punishment, and serenity. No one can find the path of grace on their own. We all have to have the assistance of the "right" priest.

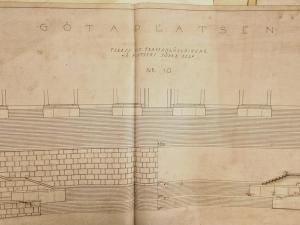

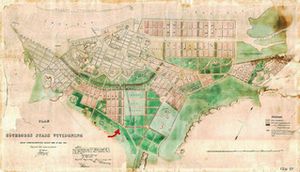

Now: How is this relevant to Götaplatsen?

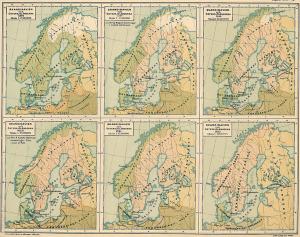

Maybe because Schartauanism had a substantial impact on the entire Gothenburg region for well over 100 years. And because this movement also traditionally had a strong appeal to members of the working class. In many areas, it became the norm openly to disapprove of dancing, theatre, and card games. A norm to reject drunkenness. But at the same time, also a norm to reject the collective temperance movement. Or the movement for women's rights or labour rights, or the suffrage movements. Consequently, these movements did not emerge as strongly in these areas as they did in the rest of the country.

Back to Götaplatsen: Could it be that "a salvation through grace" also included the rejection of a Götaplats? A place with institutions for music, visual art and theatre?

Or - was it the other way around? Was Götaplatsen born as a counterposition or counter-image to Shartaunism?

C. Scrivers, "Själaskatt", 1858.

Theology-professor Anders Jarlert, 2002.

“Svenska folket genom tiderna. Vårt lands kulturhistoria i skildringar och bilder. Åttonde bandet”, page 72, ed. Wrangel Ewert, Tidskrifts-förlaget Allhem AB, Malmö, 1939 (Public domain).

Image: Henric Schartau sculpture, Lund Arch Chapel. Photo: Maddie Leach, 2025.